|

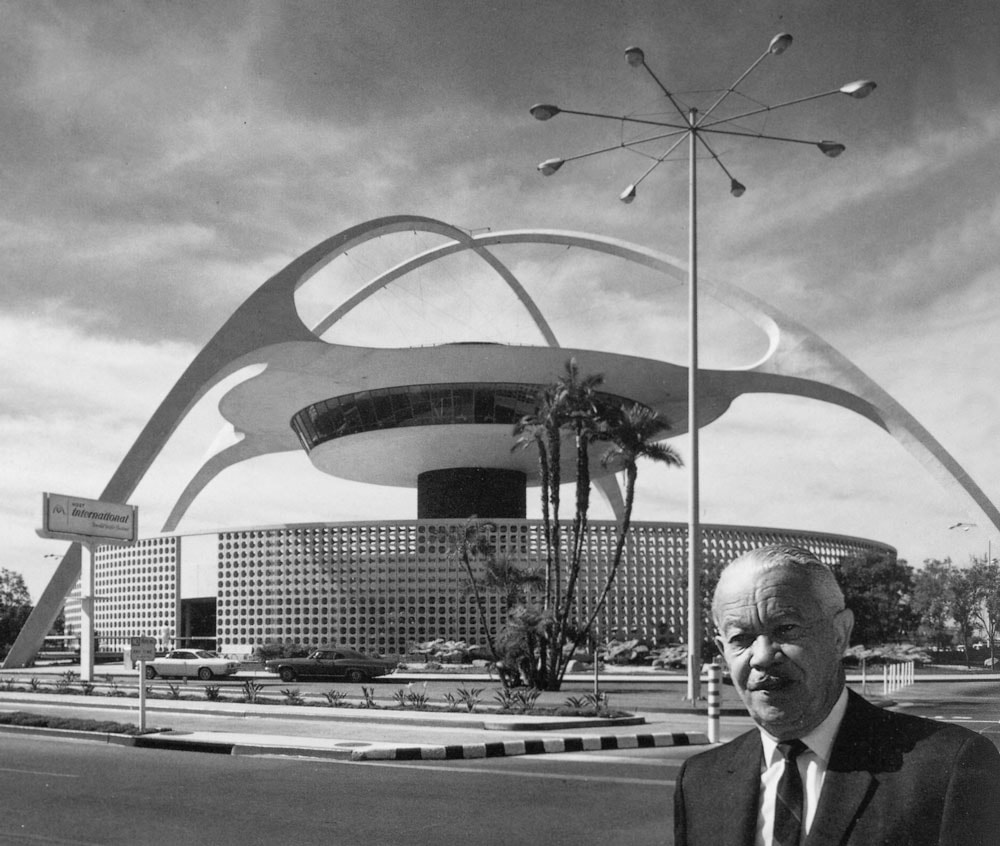

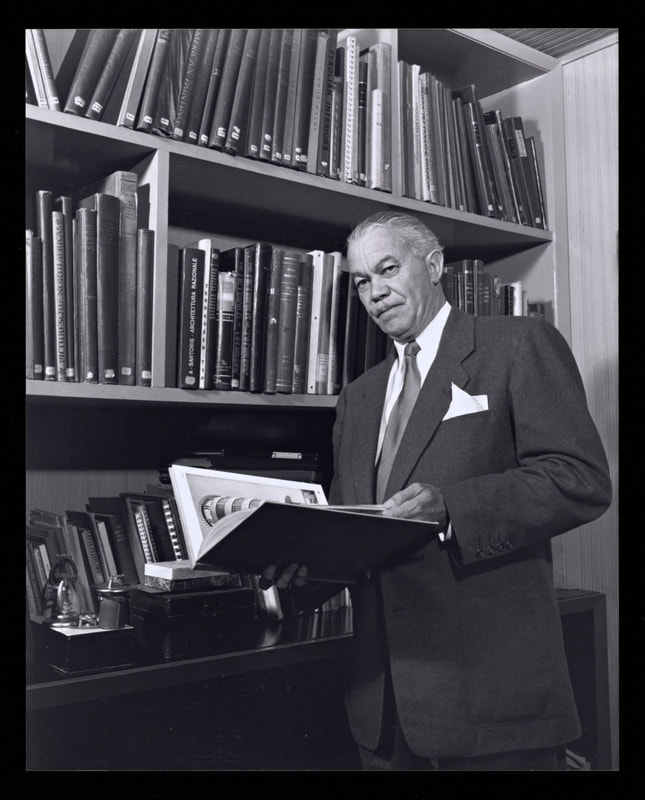

Paul R. Williams became the first licensed African American architect, who paved the way for others to pursue their dreams. By George Donovan Culture Columnist The golden dreams of California, a fruitful future of fantasies in motion, flash to life in the remarkable achievements and legacy of Paul Revere Williams. One of the single most talented among the State’s storied names, Williams, as its first licensed African-American architect, encompassed the look and feel of the Golden State through his portfolio of nearly 3,000 buildings developed and designed across Southern California. Born in Los Angeles in 1894, Williams attended Polytechnic High School, where the attempted discouragements of his teachers pushed him to channel his confidence into numerous successful appearances in architectural competitions. In 1921, he became the first certified Black architect west of the Mississippi; two years later, in 1923, he would become the first Black member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA). With his practice opened in 1923, Williams went on to prove his mastery of the City of Angels’ desires, delivering public housing, churches, and civic, commercial, and institutional buildings in the biggest styles of the time. These included Monterey Revival, Tudor Revival, and of course, the ever-popular Art Moderne, as seen in his intimate interior design for Sak’s Fifth Avenue that helped turn Beverly Hills into a glamorous retail paradise. His diversity of styles, especially amid the surging modernist tastes following the Second World War, would eventually crown him “Architect to the Stars,” with Lucille Ball and Desi Arnez, Barbara Stanwyck, Cary Grant, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and Frank Sinatra each getting in touch with him for creations. While projects and properties always provided a new, creative opportunity, the racist policies and interpersonal encounters so prevalent in American life brought trials and work challenges to Williams unseen in his white peers. Williams continued to design residences for affluent clients in neighborhoods like Flintridge, Windsor Square, and Hancock Park, places where only white homebuyers were allowed to live or make appearances around the property. To accommodate his white clients, Williams taught himself to draft upside-down when they couldn’t bring themselves to sit beside him, working on the other end of the table to present a right-side-up image. In 1949, the Beverly Hills Hotel, “The Pink Palace,” welcomed his Crescent Wing, an establishment which wouldn’t let him eat by the pool or book a room for the night, as its sheer green facade made a glitzy aesthetic standard out of his own massive handwriting. In the face of the discrimination he received in his practice and the nationwide oppression of African-Americans, Williams persevered and continued to excel year after year with new designs for most anything. Perhaps his most famous role was as associate architect on the team behind the masterplan for LAX. As the fifties’ newest coffee shops and car washes began to vaunt the exuberant Googie style, named after one of the movement’s original haunts, the airport’s incredible Theme Building, a true mid-century masterpiece, rose as the crossroads of the Jet Age, the number one place for Angelenos to catch a future on the move after other worlds’ other breakfasts at legends like Ships, Norms, and Pann’s. Outside of California, Williams donated plans to Danny Thomas, a close Hollywood friend and founder of the St. Jude Children’s Hospital, for the first building on the St. Jude campus in Memphis, TN. Upon its opening in 1962, the five-spoked children’s hospital was the first fully integrated children’s hospital in the South and would be the site of incredible advances in treating childhood diseases such as Leukemia. In 1973, Williams retired from architecture and passed away in 1980. In 2017, he was posthumously honored as the first Black architect to receive the AIA’s highest honor: the Gold Medal, for individuals whose body of work has left a lasting influence on the theory and practice of architecture. And in 2020, Williams’ archives, including blueprints, photos, and more, became digital history with the help of his own USC School of Architecture, his granddaughter, Karen Elyse Hudson, and the Getty Research Institute. Today, behind his own Golden State Mutual Building in his home neighborhood of West Adams, LA, he, along with twenty-three standout buildings from his six-decade career, is celebrated in a bronze relief. Paul Revere Williams, in his trailblazing eighty-five years, has left this country and its design languages a richer, smarter voice. The extraordinary Paul Revere Williams (Photo Courtesy of Karen Hudson) https://news.usc.edu/files/2016/05/P_194r1_web.jpg Paul Revere Williams, 1952 (Courtesy of Getty Research Institute)

https://d3vjn2zm46gms2.cloudfront.net/blogs/2020/10/27154925/WIlliamsPortraitShulman.jpg

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STAFFMadison Sciba '24, Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed